A Peaceful Tradition:

A Look Back at America’s Transfers of Presidential Power

By Eva Richards

The inauguration of President Elect Joe Biden will take place on Jan. 20, 2021.

The inauguration of President Elect Joe Biden will take place on Jan. 20, 2021.As the inauguration of President Elect Joe Biden approaches, and one of the most contested elections in American history comes to a close, it is important to recognize that, in our country’s 245 years, very few presidential transitions have been as turbulent as 2020’s.

“In large part, peaceful transitions of presidential power are all we have known in America,” said Scot Schraufnagel, a professor in NIU’s Department of Political Science. “There is danger (for our democracy) without election legitimacy. Smooth transitions of power are a big issue all over the world, but in the United States, we kind of take it for granted. Pretending that we are somehow different or better than these countries is wrong. I don’t think we are immune to this sort of problem, and we shouldn’t pretend we are.”

In fact, America’s historical peaceful transfer is important to many aspects of our democracy, including our economy.

“I think, in the past, a peaceful transition spoke of the strength of our system of government, which oversees a very important market,” said Dr. Tammy Batson, professor and undergraduate coordinator for the Department of Economics. “In many underdeveloped countries, a transfer of power from one party to another only comes with war. The stability in our system has consistently kept the United States included in the list of top economic countries around the world.”

Schraufnagel noted that President Trump’s contestation of the election result and the ensuing movement to change that result, have been a good wake-up call for Americans.

“The fact that the election result was upheld suggests that our system is working, and that is good news,” he said.

A Brief History of Contested Elections

While most elections since George Washington’s presidency had clear results and uncontentious transition periods, there is a short list of contested elections in our history books. A handful of past elections had varying degrees of contested results.

The election of 1800—between Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson and Federalist John Adams—was plagued by problems. When presidential electors cast their votes, they failed to distinguish between the office of president and vice president on their ballots. Jefferson and his running mate Aaron Burr tied, and the election was thrown to the House of Representatives as required by Article II, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution. For six days, Jefferson and Burr essentially ran against each other in the House, and votes were tallied more than 30 times, with Jefferson eventually winning the vote.

The outcome in 1800 is usually said to have cemented the idea of a peaceful transition of power.

“The election of 1800 was a hotly contested race, with lots of negative advertising,” Schraufnagel said. “John Adams lost and boycotted the inauguration, but he stepped away peacefully, and he set the precedent, really, for all times. Up until that point, there was not lot of precedent for peaceful democratic transition. What Adams did set an example for the world and was truly historical. In Europe, people were astonished that a sitting president would give up his position of power.”

The 1824 presidential election was the tenth in America, between Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and William Crawford. The election ended up in the House, leading Andrew Jackson and his followers to label the outcome a “corrupt bargain,” with Jackson going on to win in the next two presidential elections.

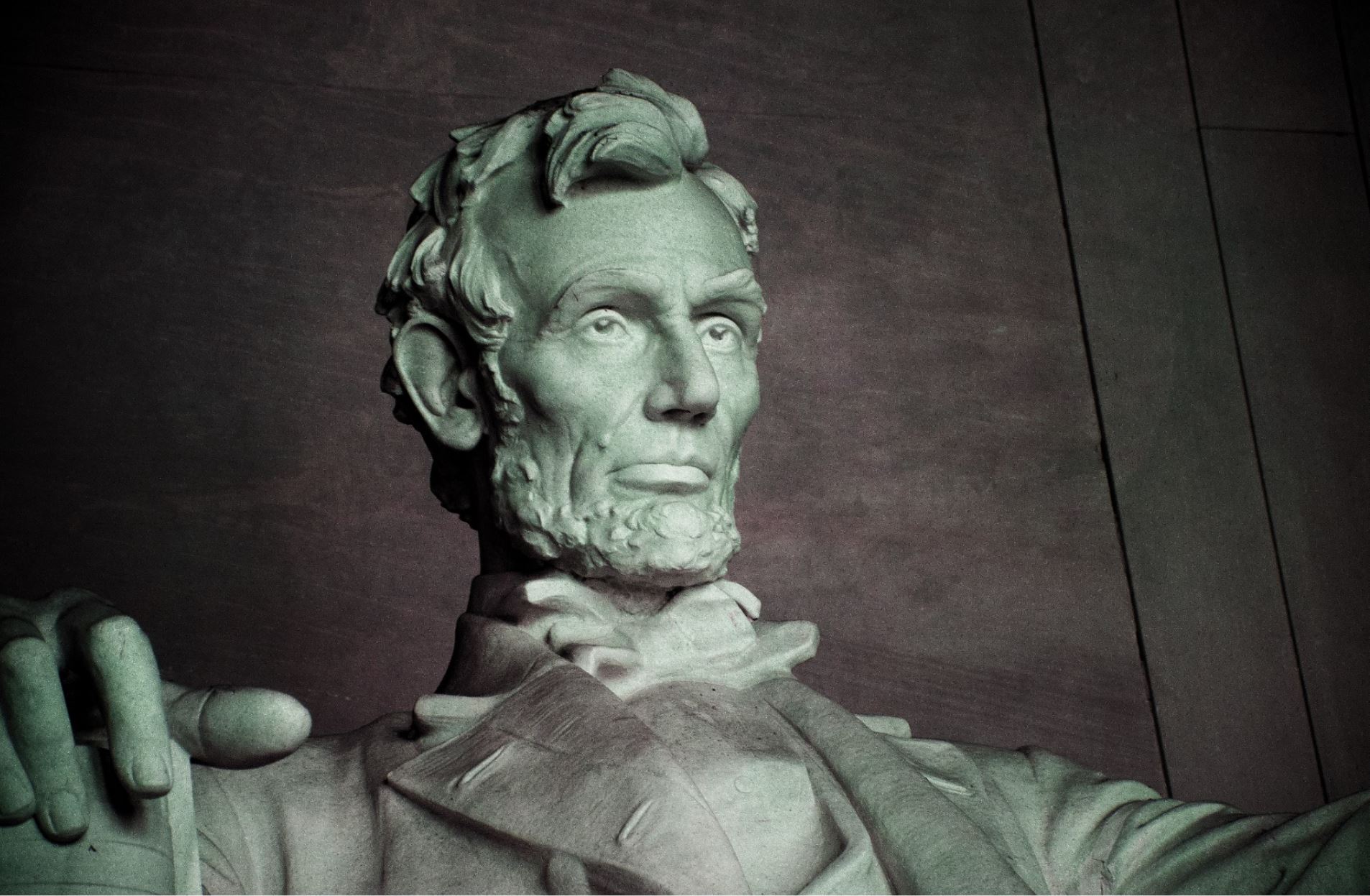

“Of course, the most direct case of failure of a peaceful presidential transition was in 1860, when secession occurred because of Lincoln’s election. The Civil War followed,” said James Schmidt, distinguished teaching professor in the Department of History at NIU.

Four other elections were hotly contested in America’s history—1876, between Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel J. Tilden; 1888, when Republican nominee Benjamin Harrison, a former Senator from Indiana, defeated incumbent Democratic President Grover Cleveland; 1960, when Democratic Senator John F. Kennedy defeated incumbent Vice President Richard Nixon; and 2000, when George W. Bush defeated Vice President Al Gore. The results of these historic elections were all much closer than 2020’s contested race. However, in all of these cases, after the initial challenging of the election result, a peaceful transition of power ensued.

“In three of those four cases, the candidate who became president only won the electoral vote and not the popular vote,” said Schraufnagel. “So, it made sense that those elections were tumultuous, because the popular vote did not win the presidency. In the fourth instance, Kennedy only received 100,000 more votes than Nixon, which is .02% more of the popular vote. That is practically a tie. In 2020, Biden won by over 7 million votes, 4.4% more than Trump, and he secured both the electoral and popular votes.”

The 2000 race is widely considered the closest election in U.S. history. On election night, the electoral votes in Florida were still undecided. Returns showed that Bush had won Florida by such a close margin that a state recount was required. A month-long series of legal battles led to the highly controversial 5-4 Supreme Court decision Bush v. Gore, which ended the recount, and Bush won Florida by 537 votes, a margin of 0.009%.

“I was teaching at that time,” Schraufnagel said. “I remember a lot of students were upset that Gore conceded as quickly as he did. He had won the popular vote. If there was ever an election that was going to be challenged, it would have been that one, but Gore stepped down.

Setting a New Precedent

It is clear that this moment is history is different. Trump’s unacceptance of the 2020 election results has shown a possible paradigm shift.

“One of the hallmarks of Trump’s presidency has been his willingness to ignore the precedents and traditions established by his predecessors,” said Dr. Ferald Bryan, a professor in NIU’s Department of Communication, who has studied political communication for more than three decades.

“Andrew Jackson was really the first populist president, and he could use some coarse language on the stump, so perhaps he is not a bad comparison (to our current president),” Bryan said. “But he could also be very suave in front of the right audience, and you never see Trump slip into a different persona. He loves his bluster and braggadocio.”

From a rhetorical standpoint, Bryan believes, Trump has largely been a one-note orator, choosing to use hyperbole and rising to his best on the campaign trail.

“Most presidents are able to rise to the moment—Reagan after the Challenger explosion, George W. Bush after 9-11, and Barack Obama at Sandy Hook, are examples,” Bryan said. “It would have been very impressive if this past week Trump could have done a 5-6-minute speech reminding us about why it is important to respect the principles of democracy.”

Bryan suspects Trump will buck tradition one last time by foregoing a farewell address.

“That tradition dates back to George Washington. In that speech he specifically denounced the rise of partisanship because it could polarize and divide the country,” Bryan said.

Still, as Americans, we must remember that peaceful presidential transitions are not guaranteed in our Constitution. Rather, our forefathers were imagining a very different system of election, where back-biting campaigns and the concept of one nominee conceding were not part of process. The original design of the Electoral College aimed for the electors to be chosen by the legislatures of their states, not by popular vote. These electors then met to select a president, picking from the “best men” among known citizens who might be eligible.

“The drafters did not even envision permanent political parties,” Schmidt said. “Popular selection of electors evolved over the early nineteenth century. Candidates did not even really campaign for president themselves. In other words, most of what we think of now as a presidential campaign, including a concession, was not even imagined by the drafters, or if it was, they were trying to prevent it.”

With Trump not recognizing this election’s results, it leaves many to wonder what comes next. Some experts are saying it only lays bare the weaknesses that already existed in our democracy.

A Symptom of the Real Problem?

“We already had a weak democracy, one in which the popular will is regularly ignored and only half the population bothers to vote,” said Rosemary Feurer, an associate professor in NIU’s Department of History. “Peaceful transitions are not the most important ingredient for democracy. Some political scientists agree that we live in an oligarchy, where money and spectacle deliver a country that is undemocratic at its core. Control by the wealthy of elections was already a core element of undemocratic governance.”

Experts like Schraufnagel and Feurer suggest that there are many safeguards our country could put in place to protect our democracy.

“We need third parties,” said Schraufnagel, who has written a book called Third Party Blues: The Truth and Consequences of Two Party Dominance, which explains the U.S.’s election laws used to prevent third parties from having much success. “The system is rigged now against third voices. For instance, the Republican party today, that’s not the whole party, but that group with more extreme views doesn’t have anywhere else to go for a party. We need more voices.”

Schraufnagel also noted that the way that we finance elections needs to be changed.

“We need to cap campaign spending. To run for the U.S. House, for instance, when an incumbent politician is retiring, you need at least $2-4 million of your own money that you’re willing to spend, or you have to have the personality type to go ask for that money every two years. So, I can’t run for Congress because I know I cannot win without (that money), and I am not willing to try and raise that amount of money. So, the type of people who are serving in Congress are either very wealthy or have the personality to consistently be asking others for money. If we capped campaign spending, it would bring a different group of people into office.”

Spotlighting these issues seems to suggest that, while turbulent transitions of power are not healthy for a democracy, they are only a potential symptom of a larger issue.

“I think it’s clear that Trump will accept the election results,” Feurer said. “We don't have to look to other countries. We have had elections where the Electoral College vote did not reflect the will of the majority, and that has been accepted and normalized, so a peaceful transition resulted from an undemocratic result. A peaceful transition is good, but if you are worried about a robust democracy, we need to think of a path that gets money and spectacle out of politics.”